Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

The final, crucial prelaunch test of NASA’s Artemis I mission to the moon was halted Sunday due to issues that prevented the safe loading of propellants into the mega rocket.

The agency’s next opportunity to begin fueling the 322-foot-tall (98-meter-tall) Artemis I rocket stack, including NASA’s Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft, is on Monday.

“We’ve fixed and we’ve reconfigured from where we were earlier today,” said Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, Artemis launch director, during a press conference Sunday. “Our team has met and has laid out our plan for how we get back to tanking tomorrow, so that is all worked out.”

The team is still troubleshooting the fan issue and is hoping to reach a solution this evening. If that goes according to plan, they will resume tanking the rocket at 7 a.m. ET Monday and begin the countdown around 2:40 p.m. ET.

The test, known as the wet dress rehearsal, began on Friday afternoon at 5 p.m. ET.

The wet dress rehearsal simulates every stage of launch without the rocket actually leaving the launchpad. This includes powering on the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft, loading supercold propellant into the rocket’s tanks, going through a full countdown simulating launch, resetting the countdown clock and draining the rocket tanks.

Operations were stopped on Sunday before loading propellants into the core stage of the rocket “due to loss of ability to pressurize the mobile launcher,” according to an update shared by the agency.

Prime and redundant supply fans for the mobile launcher weren’t working properly and each encountered different issues, Blackwell-Thompson said.

“The fans are needed to provide positive pressure to the enclosed areas within the mobile launcher and keep out hazardous gases. Technicians are unable to safely proceed with loading the propellants into the rocket’s core stage and interim cryogenic propulsion stage without this capability.”

The fans ensure that gases don’t build up and cause fire hazards or an increase in hazards, Blackwell-Thompson said.

Prior to this issue on Sunday afternoon, Artemis I weathered a powerful thunderstorm at Kennedy Space Center on Saturday.

Four lightning strikes hit the lightning towers within the perimeter of Launchpad 39B. While the first three were low-intensity strikes to tower two, the fourth strike was much more intense and hit tower one.

When these strikes occurred, the Orion spacecraft and SLS rocket core stage were powered up. The rocket’s interim cryogenic propulsion stage and boosters were not.

The fourth strike was fairly rare, because it was a positively charged cloud to ground strike and far stronger than the others, according to NASA’s weather experts.

The fourth lightning strike was “the strongest we have seen since we installed the new lightning protection system,” tweeted Jeremy Parsons, deputy manager of the exploration ground systems program at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, who has been providing regular updates all weekend. “It hit the catenary wire that runs between the 3 towers. System performed extremely well & kept SLS and Orion safe. Glad we enhanced protection since Shuttle!”

Each of the towers are topped with a fiberglass mast and series of overhead, or catenary, wires and conductors that help divert lightning strikes away from the rocket, Parsons explained. This new system provided more shielding than the one used during the Shuttle program. It also has an array of sensors that can determine the condition of the rocket after lightening strikes, preventing days of delays caused when teams have to assess the rocket.

“We don’t believe that (fan issue) was related to the storm or to the lightning event,” Blackwell-Thompson said. “It continued to run normally during the storm activities. And then it was running this morning for several hours before it encountered a problem.”

Despite the strikes and delays, team were prepared to carry on with the wet dress rehearsal Sunday until they encountered the tanking issue.

Parsons shared a reminder that this is the point of the wet dress rehearsal – working out the kinks of a new system before launch day.

“A nice thing about this being a test, and not launching today, is that we have flexibility with the test window to work through first time issues,” Parsons tweeted.

“We’re having a lot of new experiences as we set up for the Artemis I mission in particular,” said Mike Sarafin, Artemis mission manager, during the press conference. “And one of the new experiences was literally watching a 32-story-tall rocket sit out there and have lightning strike around it with this lightning protection system. It did a perfect job of protecting the vehicle.”

“The team is prepared for this, we just we just need to get through a few technical issues,” Sarafin added. “They’ve demonstrated incredible discipline and toughness, and I’m confident we’re going to get there soon.”

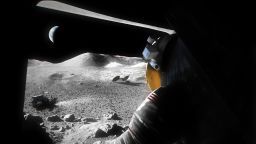

The results of the wet dress rehearsal will determine when the uncrewed Artemis I will launch on a mission that goes beyond the moon and returns to Earth. This mission will kick off NASA’s Artemis program, which is expected to return humans to the moon and land the first woman and the first person of color on the lunar surface by 2025.

What to expect next

When the wet dress rehearsal resumes, it will involve loading the rocket with more than 700,000 gallons (3.2 million liters) of supercold propellant – the “wet” in wet dress rehearsal – and then the team will go through all the steps toward launch.

“Some venting may be seen during tanking,” according to the agency, but that’s about it for visible action at the launchpad.

The team members will count down to within a minute and 30 seconds before launch and pause to ensure they can hold launch for three minutes, resume and let the clock run down to 33 seconds, and then pause the countdown.

Then, they will reset the clock to 10 minutes before launch, go through the countdown again and end at 9.3 seconds, just before ignition and launch would occur. This simulates what is called scrubbing a launch, or aborting a launch attempt, if weather or technical issues would prevent a safe liftoff.

At the end of the test, the team will drain the rocket’s propellant, just as it would during a real scrub.

Depending on the outcome of the wet dress rehearsal, the uncrewed mission could launch in June or July.

During the flight, the uncrewed Orion spacecraft will launch atop the SLS rocket to reach the moon and travel thousands of miles beyond it – farther than any spacecraft intended to carry humans has ever traveled. This mission is expected to last for a few weeks and will end with Orion splashing down in the Pacific Ocean.

Artemis I will be the final proving ground for Orion before the spacecraft carries astronauts to the moon, 1,000 times farther from Earth than where the International Space Station is located.

After the uncrewed Artemis I flight, Artemis II will be a crewed flyby of the moon, and Artemis III will return astronauts to the lunar surface. The time line for the subsequent mission launches depends on the results of the Artemis I mission.